The chiaroscuro image of a child lying on the sidewalk, covered with a white cloth, a crucifix, and a burning candle on his chest, made me close my browser with a gasp. His little shoes took me back to when I was seven and witnessed my younger brother's lifeless body lying on the ground, covered by a white sheet.

At first, I turned away from the other photographs by Sylvia Alonso, now exhibiting at Casa Chihuahua (https://www.casachihuahua.org.mx). I thought her stunning documentary photography of the tradition of Los Seremos was disturbing. I thought a staging of the most devastating of losses, the death of a child, was macabre. I thought my mother would have burst into tears.

Los Seremos ("So shall we be") is a centuries-old tradition that honors deceased children in Valle de Allende, a city in my native state of Chihuahua, Mexico. People believe—or suspend their disbelief—that the souls of departed angelitos, little angels, come down to earth on November 1.

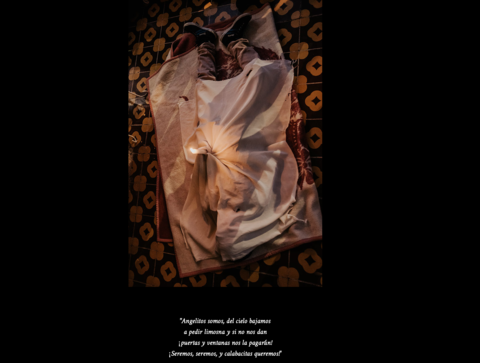

The ritualistic performance takes place at the end of the day, under twilight. Small groups of children go door to door, staging the wake of a dead child. A child lies down on the sidewalk with their head facing a house's door and pretends to be dead. Other children cover the "dead" with a white sheet and place a crucifix and a candle on the child's chest; sometimes, they also place flowers. The children then kneel around the child, light a candle, and say an Our Father and a Hail Mary. After ringing a bell, they sing loudly, "Seremos, seremos, y calabacitas queremos" (So shall we be, so shall we be, and we want little squashes.) They say they're angelitos and threaten to break doors and windows if their demands go unmet.

At the end of the performance, the children laugh and cheerfully receive treats before moving to the next door. But all along, the adults who chaperone them make sure the little ones perform the ritual with respect and reverence toward death. There is transcendence here.

This local custom is one of the myriad ways we Mexicans celebrate our dearly deceased. A day or more when we mourn and remember them to keep them alive somehow. A sacred time when we stop working to acknowledge the inevitability of death. But also a festive pause to appreciate how magnificent life is in its brevity.

I tried to turn my back on the feelings Sylvia Alonso's striking photograph stirred in me. Still, I later realized that rather than being macabre, Los Seremos is awe-some. It made me feel that rare and dumbfounding emotion that takes us out of the mundane: Awe—a tangle of wonder, amazement, and admiration muddled up by fear, dread, and horror. The celebration teaches children about death and reminds adults how precious and fragile a child's life is and how deserving of respect and reverence.

My mother would have burst into tears. But the celebration should give a healing, cathartic respite to parents like her, who buried a small child. Alonso's photographs prompted such an exquisite moment for me.